Non-Fiction

I am not—I think I am not—afraid of dying.

~William Maxwell, Nearing 90

. . .

Missing cat, panic, braindead, fruitflies, envy. Problems.

As a psychotherapist, I worked for years to help people solve their problems. Then I learned that, according to Buddha, we all have 83 problems. Everyone: Bill Gates, Oprah Winfrey, even the Dalai Lama, though he doesn’t seem to mind. And, this Buddhist parable goes on to say, if you solve one problem another will inevitably take its place. Eighty-three. If I had known this before I took up psychotherapy, I might not even have started. Or I might have understood that my job was not to help solve problems, but simply to help. In any case, when I gave up my practice after twenty-five years, I did not give up my interest in problems but I did take a new approach. Now I collect them. It’s easy. I ask, and people give them to me. One woman even wrote out in longhand her list of 83 problems and sent it to me in the mail.

A. Alopecia, apepsia, arthritis, apnea, athlete’s foot, asthma, acne. These are medical, afflictions of the body. Aspergers, Alzheimers, agoraphobia: afflictions of the mind. Alcoholism: your choice. Things which can be diagnosed* are usually accepted as problems, conferring upon their sufferers sympathy. Usually—see Alcoholism. But I have also collected ambition, angst, ankles, ants; more ambiguous problems which may engender something other than sympathy.

Once, when I was in Oms, France, and terribly homesick, I spent a sunny afternoon on a sweet little concrete patio watching cartoonishly large ants pick up chunks of salami and carry them into the heather, pausing only for antennae discussions with ants marching the other way. I was so grateful for those industrious, beautiful ants. They grounded me; they calmed my heart. In the morning, I even watched them from bed with binoculars. You could say ants saved me.

So I love ants. When my daughter, Chloe, complains about the ants in her driveway (not even in the house!) I have to fake sympathy.

_____________________________________________________________________

*Italics denote a problem. For some readers italics are the problem. In any case, some of these problems have been collected and some have been designated by the author, my choice. But one can start to see everything as a problem; it depends on your mood. In the course of revision, I had to do some radical de-italicization. Feel free to debate, or to add italics of your own, in your mind.

___________________________________________________________________________

B. Bicycle messengers; beauty; body.

Bush, Do-You-Miss-Me-Yet-George W.

Remember him? Randi asks. (Randi is my ex-office mate.) Do you think George Bush was actually insecure? Yes, Randi, George was insecure, I say. I am opinionated. Randi isn’t sure. I say, Oh, come on. The reflexive combativeness, the bombast, that smirk. Those minesweeping eyes vigilant for ambush. Those rolled up sleeves, those hands on hips, Randi says. (Randi calls us TOHB’S, pronounced toobs: Trained Observers of Human Behavior.) The leather bombardier jacket. Compensation, we say in unison. Ever watch him take a swing at a golf ball? How he tries to laugh it off? He didn’t experience his insecurity, so he didn’t have to suffer from it. We did. Beware the unconscious leader, Randi says.

Bullies, boredom, blahblahblah.

C. Can’t: think, cry, come. Can’t feel my toes.

Clicks, from my brother Bruce: No, listen, he says. Seriously. My car does this thing where it won’t start. I try it, click. But it’s intermittent; it starts, it starts, it starts, then for no reason, it clicks. I took it to the dealer and they couldn’t find it—if it doesn’t click for them, they can’t fix it. The next day I had to try it over twenty times, click, click, click, click, click. When it finally started I drove directly to the gas station and he said it was the battery, which he replaced, and it started fine. For a few days. Then, click. I feel like my car is the enemy, he says. I can’t sleep with it lurking in the driveway waiting to defeat me. I don’t know what to do. I tell him I can’t help him. Cars are a problem.

Cowards. Caterpillars. Cats.

D. Death. According to Buddha, Number One Problem.

We don’t even like to use the words: to die, death, dying, dead. Instead, we say croak, pass, go over, breathe your last; give up the ghost, kick the bucket, cross over Jordan, join the angels, hop the twig, meet your maker, depart this life, reach the finish line, transition to the next phase, peg out, bite it, flatline. You are done, called home, expired, released, laid to rest, no longer with us, taken by God, on the other side, pushing up daisies, six feet under, terminated, rubbed out, cashed in, snuffed. You are no more, you are singing with the angels, you are sleeping with the fishes, you are cooking for the Kennedy’s, you are gone to your reward; translated into glory, gone to the final resting place, or to the world beyond. You have bought the farm, transcended this life, found everlasting peace, crossed over into campground, shuffled off this mortal coil, left this world, left the building. The big sleep…should something happen. The race is run. May you rest in peace.

But be careful about euphemisms. Euphemism can signal denial.

If I could talk to Buddha, I would tell him that, in a complete turnaround, my mother on her deathbed became sweet, willing, generous, funny (well, she was always funny), helpful, tranquil, lovable, loving, and hopeful. Hopeful. Her turnaround, her death, changed my life; it made me a better person. Of course, it wasn’t my death.

E. Eggs: who knows how long they’ve been out there?

Eavesdropping. My husband and I were driving to the pub for our Thursday night pint and I was kvetching about a dear, difficult friend when my phone butt-dialed her. Four times. She eavesdropped. She finally called me back to tell me. I was stricken, until she mentioned that at first she wondered if I was mad at her but then she thought I must be complaining about my mother-in-law. But eavesdropping is a great way to collect, so I do it. People on cell phones give it all away: Sherry’s ridiculous torpedoes (Whole Foods); Robin’s humongous rock (Nordstrom); I love you but I’m not in love with you (Voila Bistro); Do YOU have my driver’s license? (SeaTac Airport); Fucking bullshit fascist hoops they fucking make you fucking jump through. (Medgar Evers Community Pool Women’s Locker Room); Give-it-to-me-give-it-to-me-give-it-to-me, baby. (Kinkos). This kind of eavesdropping is irresistible, and also unavoidable. But eavesdropping on your wife, your teenager, your neighbor, your co-worker, or your law-abiding citizenry, is a problem.

F. Fuck, fucking, fucked. I refer to the word, not the activity.

Don’t say fuck. Fuck is a problem because of its effect. People experience this particular word, as well as other four-letter words of Anglo-Saxon extraction, as an assault. Once you say fuck in casual conversation, never mind formal discourse, you have agitated listeners, signaled disregard for propriety, called into question your thinking as well as your judgment, sewn seeds of hostility, inserted unwelcome, perhaps unwholesome, thoughts of sexual activity, and severed sympathetic connection. Your line of reasoning will be buried in dirt. Don’t say fuck.

Except sometimes. Sometimes fuck is exactly the right word. When you’re in a tight spot, ‘we’re fucked’ lightens the load. Fuck can make you laugh. And fuck may be the only way to join with an otherwise alien culture (the 22-year-old gnarly boarder who rescues you, granny, from the precarious snow ledge you cling to after your fall from a chute you had no business skiing). The only way to provide the punch in a punch line, to give yourself a bit of naughtiness, especially if you are female and getting on in years, to express misgiving, as in wtf, or excitement, passion, despair.

One time, when I was seventeen, I slipped into my parents’ bedroom after a date and I found my mother alone in their bed, drinking. Hi, I’m home, I said. Your father is out fucking some other woman, she slurred. My mother did not swear. This word told me everything about how bad things had gotten.

G. Greed, greedy greed.

The letter g, gone from participle and gerund. Dolly Parton’s abandonment of g—Darlin’!—is adorable. Tommy Lee Jones can do it and sound smart. My beef is with those guys who drop g’s in that fake dumb way. Since you will only go the route of sounding fake dumb—folksy—if you believe you are smarter than the rest of us, dropping your g’s signals condescension. You think we don’t get it? The worst offenders? Not those previous presidents, not those sports-radio-talk-jocks, but those therapists. So I’m feelin’ a little angry that you just threw my ashtray at me. Are you willin’ to talk about that? Not only fake dumb, fake calm. I’ve heard it more in male therapists. Maybe they worry they have a little dominance*, aggression, and competitiveness to disguise.

Genius, no fake-dumb about it. According to my-father-the-rocket-scientist, everyone else was stupid. The religious were stupid—just kidding, he meant unschooled in science; the rich were stupid—just kidding, he meant lulled by money into lack of ambition; and the Democrats were stupid—just kidding, he meant stupid. Chuckle chuckle.

________________________________________________________________

* Unless you are a counter like me, you probably did not notice, but we have now reached 83. And we are only part way through the letter “G.” But remember, Buddha did not say 83 problems in total, he said 83 problems per person. The total is infinite. Buddha also claimed there was an 84th problem, as universal as death. It is the only problem with which he can help: our desire to not have problems.

______________________________________________________________________

H. Hiccups, haste, hostility, holidays, hellfire. (I sometimes had to question the sincerity of my respondents—“hellfire” from a happy gay man at Octoberfest?)

Hobbyist. My neighbor Robert, who polishes his wife’s limos across the street from my garage/studio every day, called my artwork a beautiful hobby. Now that is the worst thing you can say to a serious artist and I bristled (covertly. I love Robert.) But then I thought about it. I thought about work and identity.

Happiness, habits, handkerchiefs, hysteria, my haircut. Head lice—it’s not funny.

I realized that, as an ex-psychotherapist, I still have a certain response to problems—other than writing them down, I mean. I help, I try to solve. I can’t help myself. And it’s great. I feel useful, and I get to stay out of the deep end. My point: now my problem-solving is more like a hobby. Hobby: “favorite pastime or avocation;” “activity that doesn’t go anywhere,” i.e., done for its own sake, for the love if it. It may be that if all your work is hobby, and beautiful, you have found a state of grace.

I. I squander my thoughts, I can’t commit to anything, I hoard.

I—meaning you, meaning me. Ego. A problem. Individual rights, entitlements, achievements, accumulation, consumption. Sharing is difficult. Getting in line, taking turns, helping out, blending in, are difficult. I becomes me me me. But the ego in the I is also humanity’s transcendence. Without it, we do not get Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” Picasso’s “Guernica,” Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.”

Inertia, indecision, something icky on the toilet seat.

Invasives. When I suggested reintroducing California condors to the eastern slope of the Cascades, the biologist in the family looked long-suffering and said, I don’t think that would be compatible with the ferruginous hawks we’re trying to re-establish. I did not press my case, though California condors had lived on the Eastern slope of the Cascades until 150 years ago, until the human invasives eradicated them.

Infinite Compassion. I saw the Dalai Lama at a conference on compassion. He said love is biological (protection) and anger is biological (protection). (The compassionate psychologist panelists did not appear to appreciate the anger part.) If you take birth as a human, he said, it is good to keep love 24 hours a day and anger only occasionally. If you take birth as a turtle, you don’t need love, only anger. He thought this was very funny. He said he might come back as a turtle.

J. Jesus. Jesus is not the problem. What Jesus said, what Jesus did, what Jesus stands for, is not the problem. Ditto the Prophet Mohammad.

K. Kudzu: it ate my shed, the abandoned barn, my pasture and my wood lot. You don’t want Kudzu. You don’t want any non-indigenous plant or animal that adversely affects the habitats it invades (see invasives.). Milfoil, zebra mussels, Mediterranean snails, starlings, sea squirts, tansy ragwort, thistle, pampas grass, scotch broom, English ivy, eucalyptus Himalayan blackberry.

One time, squeezed into a little bedroom awaiting the birthday boy at a surprise birthday party, I whispered to a friend how much I loved her little eucalyptus tree. A woman pressed up against my back hissed that eucalyptuses crowd out natives, burn like dry straw, and are a blight on the face of the earth. (Tell koalas that.) She meant I should not love eucalyptuses. But how can I not love eucalyptuses? Eucalyptus means picnics in Griffith Park, bare feet on slippery leaves in sandy canyons with my brothers, sun. It is not the eucalyptus tree’s fault it thrives in California, where it was brought by entrepreneurs hoping to make a killing with this quick-growing tree. (It grew quickly all right, but too knotty and twisted to make railroad ties.They brought the wrong one.)

By the way, biologists revere natives—GOOD—and detest invasives—BAD. It is black-and-white for them. I admire biologists as much as I admire anybody, but I find their position problematic. The banana slug that overnight mows down my tender row of romaine is a native but I will have to be a much better Buddhist not to kill it. Of course, I’m not native to Seattle. I’m from California.

L. Love, lack, loss, limits, landfills. Lipstick: every time—every time—I find a color I like, they quit making it.

Liars. My personal Number One Problem.

People lie. I know that. But I look at liars the way an ophidiophobe looks at snakes: with fear and loathing. So much fear and loathing, in fact, it is as if this creature cannot exist. It becomes exotic. It fascinates. John Ehrlichman, Oliver North, Ronald Reagan, Clarence Thomas, Bill Clinton, Jeffery Skilling, Donald Rumsfeld, Alberto Gonzales—I watched them all. Their dissembling was entirely transparent, yet their demeanor remained righteous. Apparently, lies no longer exist. Because there is no such thing as facts.

Lost keys, lost love, lost track of my life.

Not all lies are equal. Look at the language. Many words for the lie are mild, even whimsical, like humbug, twiddle-twaddle, taradiddle, flim-flam, clap-trap, cock-and-bull, lip-homage, mouth-honor, eye-wash, window dressing, moonshine, mare’s nest. Some reek with the lie’s bad faith, like perjury, forgery, mendacity, double-cross, falsehood, fraud, deceit. And some words rely on context to measure the lie, like exaggeration, equivocation, invention, guile, cajolery, flattery, fable, yarn, hypocrisy, pretense, evasion, farce, dissembling, distortion, cant, canard, subterfuge, quackery, flattery, sham, insincerity, dissimulation, bosh.

What kind of lie is the non-answer?

M. My mother. Reported by many as their Number One Problem.

Motherhood: my kids ruined my life. Then they say they were joking.

Moods, mean people, mold, masculinity.

Meat: I think cooking meat is just beyond me.

This from a man slumping into the kitchen after checking the steaks on the new gas-fired barbecue. A man whose father melted the side of the garage with his new gas-fired barbecue at the first meeting with the prospective daughter-in law, causing quite a lather in mother, father, and son, though not in the prospective daughter-in-law, who did not care about the meat, really, though she wished she weren’t such a bother. Still, that father insisted on firing up his barbecue on the Fourth of July, Labor Day, and every Sunday afternoon—with his lips compressed and his shoulders tensed—for thirty-odd years, though he never got it right. Even when the meat turned out, he suffered.

This suggests the meat problem is genetic. But there are things more important than meat, or moaning about meat. Like doing the right thing, or trying to do the right thing. Like honoring your father. I married the man.

N. No willpower, no heat, no sex, no tomatoes, no newspaper, no money, no rain, no hope.

For many people, just the word No is a problem, unless the question is, do these pants make me look fat? Except Joan. Joan said, No problems. I have a steel door, like those huge doors on gothic cathedrals with a bunch of brass rivets and heavy round handles? And I keep all my problems behind that door. I throw them over the wall or something. I don’t want them—why would I open that door?

Never lived up to my potential, nothing to devote myself to, nostalgia.

Joan reminded me of Sherry, who said her only problem was to Be Aware of God in Every Moment and Still Be in the World. I was astounded: she lived alone, could not make her rent, had no retirement, no prospects, no plan, and she was looking at sixty.

O. Outrage (theirs, mine).

Out of: ideas, clean socks, luck.

Obsession: she texted me 48 times in, like, fifteen minutes.

Occupation—another number one problem in my collection.

Overwhelmed by problems. There is something comforting about Buddha’s 83 problems, a leveling effect, as if we are all dealt the same hand. But this does not seem true. I can see that every life contains suffering. But in equal part, every life? Life is unfair seems more true. Fair or not, I am experimenting with managing my 83 problems—and limiting rumination—with a strict list. Only 10 per day. For example, today my problems are my neighbor’s morning glory, not enough time, the light fixture in the bathroom, email, the other neighbor’s vine maples, my dog’s teeth, finding a new shower curtain, returning wrong-color paint, finding the AAA statement, the downstairs closet. See, I’m not even thinking about my son’s substance abuse, his marriage, one grandchild’s anxiety, my mother-in-law, my daughter’s slide into postpartum, the pain in my fingers, the smell downstairs, how long my money will last, how I looked in the mirror this morning, a dying friendship.

P. Photographs. Some images cannot be erased.

One photograph depicted naked brown men, stacked, on a dirty cement floor, heads shrouded in black pointy hoods resembling the white hoods of the men of the Ku Klux Klan, though the men of the Ku Klux Klan were never, by their own bylaws, brown men. One photograph depicted naked brown men with naked buttocks in the air, unprotected, exposed, poised for derision, or intrusion. One photograph depicted naked brown men forced to masturbate in the faces of other naked brown men as American soldiers grinned, or took pictures, or passed by without notice. One photograph depicted a naked brown man cowering, trying to protect his legs and his genitals from three lunging, snarling German shepherd dogs, dogs eager to do their duty with the naked brown man, barely restrained by laughing American soldiers. Some were bloody. One was dead, a naked bruised body in a body bag with ice on his chest. One naked brown man was being dragged by a dog leash around his neck, dragged on hands and knees across the dirty cement floor, dragged by a grinning female American soldier, thumbs up.

Q. Questions.

If you accept that you, and everybody, has 83 problems and will always have problems, how do you keep from giving up?

What is the benefit of naming problems?

Has therapy made our problems better? Worse?

Would a person be lonesome without her problems? Bored?

If you do not think about your problems, where do they go?

Are your problems better—more valid, sad, shocking, profound—than mine?

Why does it make one feel better to hear about someone else’s problems?

How do you maintain compassion when someone’s problems seem self-made, self-sustaining, and damaging to others?

If you believe that massive world problems—flood, famine, war—will always exist, and that one person’s efforts cannot ease these world problems, what do you do?

How can the Dalai Lama giggle when asked about China?

R. Righteousness. Righteousness has led to polarization, name-calling, retaliation, stalemate, distortion, abuse of power, war. But passionate people tend to be righteous. Some of them I admire. Perhaps it is righteousness plus power plus insecurity plus no capacity for empathy that makes it deadly.

Religion. During an interview about the restoration of native prairie grass at her stunning ranch in Crawford, Texas, Laura Bush was asked, gingerly, if she ever felt guilty about having so much. Well, she said, I am grateful every day. But I also know that every single person in the world can go outside and enjoy God’s beauty just as I do. I question that.

The Dalai Lama said religion has failed us. He said its effect, at best, is limited. He snickered; he said he was just a poor monk. But we must use our common sense, he said; we must use our intelligence! We must look to science for answers to the terrible, man-made problems we now face.

Regret. This from a 66-year-old man whose life-threatening cancer is miraculously under control: I know I should be happy. But the funny thing about dying—or almost dying—is that it made me realize I’ve been an asshole all my life. How can I change all that?

S. Sentiment, hackneyed: “When I am old, I shall wear purple.” That just pisses me off (spleen).

Sorrow. My problem is not the death of my child; my problem is this terrible sorrow.

What can be done for the broken heart? In the newspaper, we read about people seeking comfort through retribution (sometimes mistaken as closure) but what kind of comfort does retribution provide? And what happens a year later? We don’t read about that. Religion tells us forgiveness provides the only true comfort; love thine enemy. People on their deathbeds exhort us, time and again, that love is all that matters. But I wonder if forgiveness for terrible injustice is one more unattainable state. And yet, without it the heart dies, as if corroded by poison. I read about a family in Eastern Washington, devout Mennonites who lost their five children in a horrific car crash. The father of those children and the driver of the pickup that crossed the center line and hit their van head-on were hospitalized in the same small hospital, and the father initiated a visit while they were both in rehabilitation. Now, five years later, the mother and father have two little children. They see the other driver regularly, and they try to help him out. They say it is hard sometimes, but they pray. Forgiveness is a practice, not a feeling.

T. Time—too much, never enough. From my oldest friend: It goes fast, doesn’t it? We did not know, could not have known, that she would die three years later, at age 70, of a sudden, devastating septicemia.

Trains. A slender fourteen-year-old stands on the shining steel track. She laughs, she flips her arm, she rakes her fingers through wavy red hair. They are not supposed to, but kids cross these tracks all the time to get down to the beach. Had she simply stopped to finish a story? When do they see it, her girlfriend, the two boys? A neighbor grilling steaks on his deck saw it. The girl’s house is almost on top of the tracks. Her mother made it to the scene as the aid cars screamed up. But didn’t she hear it? is what everyone said, stunned and bewildered. Wake up, baby. Please wake up, is what the mother said, her nose pressed into the girl’s neck. I read about this in the paper. This mother had been my client. I called and left condolences with the person screening her calls. I sent a card. Then I waited, anguished. I did not know what to do. My rulebook said that since she was no longer my client, I should let her contact me. It felt wrong, and still I waited. Seven years later she called me. When I told her how sorry I was, sorry for her loss and sorry that I didn’t do more, she waved me off. Then she said the kids had been warned a million times not to cross those tracks; it takes only four seconds for a train to hit that spot after coming around the bend. (When she threatened to sue, the county fenced it.) She told me that stuff in the paper was bullshit, it made her mad. She never said wake up baby. She resuscitated, even though she knew her daughter was dead. And she made the EMT’s resuscitate, for two hours they resuscitated, until the father could get there, until she was ready for them to stop. She said it was the least she could do.

U. Uncultivated souls, uncontrolled urges.

Unlimited choices. Research shows that a person’s number of choices is inversely correlated with happiness. More choice equals less happiness.

Underwear: I have to go to Nordstrom’s today to buy new underwear. Even thinking about it makes me tired.

This problem might sound petty. But this woman suffers from lifelong bouts of depression exacerbated by childhood sexual abuse. She hates her once-beautiful body, thickening and slumping with age, and she is married to a difficult man who uses sex—and her fear that she is unlovable—in a coercive way. Not that she uses these troubles to get sympathy. These are my observations. So I try not to judge. The underwear, the malaise of shopping at Nordstrom’s: it’s a metaphor.

V. Vermin: gulls, crows, and rats. I only give rats a problem designation because I like gulls and crows, though if I were consistent, I would call none of them a problem, because they all try to take care of garbage generated by humans. Or I would call all of them problems because of their work as disease vectors. But then they’re a curb on human overpopulation.

Victim. Drink too much? Gambling problem? I wish my Mama would have loved me, the blues artist R.L. Burnside moans.

W. Warming, global. My friend John-the-zealot declares there are no longer personal problems. None. Only GLOBAL WARMING.

Wishful thinking. Bad in a sailor. Once, on a trip across the Mediterranean, I puked for twelve miserable hours because the captain of our sailboat took the best possible interpretation—in fact, better than possible—of the projected weather forecast (25-35 knot winds and a Beaufort scale, meaning seas, of 4.5-7). He claimed they exaggerate, and after some imaginative number-crunching, showed how conditions could be perfect for a bracing, one-in-a-lifetime sail. He forgot to mention the shifting winds. Wistful wife, wimpy husband. Which caused confused seas, so that we pitched not only up-and-down but side-to-side and all around in the gale-force winds and ten-foot waves, which besides making me sick unto death, attempted to sweep the captain and my husband off the stern. Alas, that their jacklines held.

Willfully incompetent in-laws. No, only GLOBAL WARMING.

X. X -therapist, -husband, -president. It is difficult to be an ex. You have so many habits to confront, things to change. You may not know how to act in many situations. You may behave poorly.

Y. Yelling. My mother always yelled at me and now I can’t stop yelling at my kids.

Loud display, even of positive feeling, seems to be unattractive and unwelcome, especially if the person yelling is female and getting on in years.

Yes: I might have said yes to one too many Top Pot doughnuts. (Cf. uncontrolled urges.)

Yearning. Robert Olen Butler tells us there is no fiction without yearning. The character must yearn for something or, no matter how well the story is written, it will be flat. Uh oh. I thought yearning led to disappointment and envy. In fact, very early on, I stripped myself, not only of yearning, but most feeling. I became excellent at rising above, making do, not caring. Who could tolerate a steady state of dashed desire? But Robert Olen Butler is talking about fiction. And anyway, I have been padding feeling back on. I really want a new house.

Z. Zen. Not native.

Student: “Not even a thought has arisen. Is there still a sin or not?” Master: “Mount Sumeru!”

The idea, I think, is that if you tangle with nonsense, your brain will take a leap and free itself from the chains of logic. But what is the purpose of the abandonment of discursive thought? Does it lead to being in the moment? To acceptance, the solution to the 84th problem? Zen koans don’t help me; they make my stomach tighten. I wish the Dalai Lama could have helped me. The Dalai Lama laughed about his teacher’s yellow whip when he was a five-year-old Dalai Lama-in-training, saying fear helped him learn. Ah. The Dalai Lama laughed about death. Ah. (But be careful about sharing the good news that we are all going to die.) But the Dalai Lama did not say a word about zen koans. For that, we’re on our own.

“83 Problems A-Z” first appeared in the Jabberwock Review, vol. 33.2, Winter 2013.

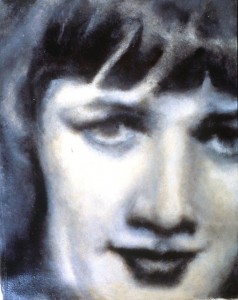

Barby (1919-1997)

Those ashes. I hadn’t expected to love them. The twelve-inch square box, the glossy white paper. How heavy they were. That’s the bone, they said. In the car, I shook the box, and the bone rattled.

At home, I scoop some out. The powder in my hand is dense, not dusty the way wood ash is, and it is infused with tiny slivers of bone that remind me of Stone Age needle-tools. I take another handful. The ash seems to contain something like life, but the opposite of warmth. I seal my purloined ashes in a sandwich bag and lay it flat in my desk drawer. Then I rewrap the box, tape it shut, and tuck Barby’s ashes into a canvas carry-on. I am flying south to California to meet my brothers.

On the way to the airport, I shake the box again. The bone rattles.

Barby was my mother, but I always called her Barby. Many people begin calling their parents by first names once they grow up, a rite of passage, but in my family it was Barby and Dick from the beginning. They said my big brother Bruce started it when he learned to talk and they just let it be. Everyone called her Barby, my friends, her friends, our teachers, the cleaning lady, the kids on the block; milkman, mailman, garbage men. Because she came before the doll, I never associated her with all that. Anyway, the doll spelled her name B-A-R-B-I-E, and, except for the same noteworthy breasts, that vacant-eyed airhead was nothing like my Barby. My Barby smoked cigarettes, drank martinis, and was really really smart.

Later, the grandchildren called her Barby, too, but by then she wasn’t the same person.

We are meeting at David’s place in Del Rey Oaks, near Monterey. We plan to rent a car and drive down the coast to Santa Monica to release Barby’s ashes into the ocean. No one knows whether or not this is legal, but that is the plan. We are not exactly close. This will be our first gathering since Barby’s seventy-fifth birthday, three years ago in Knoxville, Tennessee.

A quick introduction. Barby was a housewife and Dick was a rocket scientist, and they were married for twenty-six years, from 1938-1964. After five years of unfettered, young-married fun, they had four children: Bruce, me, Geoff, and David. For most of my 1950’s childhood we lived in West Los Angeles around the corner from the sprawling Douglas Aircraft plant where Dick worked on a busy street called Bundy Drive. Sprinklers, sidewalks, and stucco ramblers.

In the fall of 1963—Bruce was in college, but the rest of us were still at home; David, the “caboose,” was barely ten—things fell apart. Dick went to Huntington Beach to live with his girlfriend and Barby went crazy.

Neither of them ever came back, not really.

Black Dog backwards. Barby flung the skirt of her shirtdress over her head. She would not come out; she would not cover her exposed underwear and skinny, bruised legs, askew on the rumpled sheet. Black Dog backwards, she rasped from under the thin cotton, over and over and over. They called it “nervous breakdown.”

The sun is out in Monterey. We have come from deep winter: Bruce, a scientist at NASA, from Cleveland; Geoff, a physics professor, from Knoxville; and I, a private-practice psychotherapist and visual artist, came from Seattle. David, a math professor, is the lucky one who lives here, where you get spring in January.

We assemble in David’s bright living room on two sectionals and the sole family heirloom, a spindled mahogany rocker. It occurs to me to put my glossy white box on the coffee table, but I don’t. Dust motes jounce around in the late afternoon sunbeams. We always do this, some delicate shuffle, like dogs creeping around corners to sniff and sneak peaks. Sometimes, in the course of our get-togethers, we soften up. I know we try. I had wondered if it would different with Barby gone, but this feels the same. I feel responsible for (and incapable of) making things go well, and I prattle, brightly, into the air.

David hops to the kitchen and returns with a bottle of champagne. I watch his handsome hands, square like Dick’s but with more refined fingers like Barby’s, as he unwinds the wire. His left-hand nails are short and the right-hand’s long, for guitar and bass. He pours the cheerful, light-amber liquid and we raise our flutes. No one says Barby, but it’s to her. Then we all chat, about weather, wine, travel, nothing.

Bruce steers into our past. He complains about the derision, the neglect. His face, in any case pinkish, flushes deep rose, and his lips are stiff. I stare at Bruce’s thick wavy hair, shiny-aluminum in a sunbeam. Barby loved Bruce’s glorious hair, the wave and the widows-peak. I don’t think Dick did. Dick was bald. Bruce says there was some weird overlay of sex in our household. He says we were abused. We have talked about all this before, but I am no longer interested.

I was there when Barby died. If she had just died suddenly in her sleep, like Bruce I might have still been mad, if not about our childhood then about the long years after, thorny and stingy. And I would have been sad. I would have been relieved. But Barby didn’t die suddenly in her sleep. Barby spent her last days tucked in my house, in my bedroom, and something I could not have anticipated, or even imagined, happened. We fell in love.

You never know, Barby-the-athiest said, two days before she died. She was talking about heaven, about joining her mother there. She smiled into my eyes, a brave girl going off to her first day at kindergarten. You never know.

I cannot expect them to feel the way I do. They weren’t there. I tried to tell them over the phone last September how sweet she was at the end, but I got the feeling they found me irritating or disloyal. But if you walk off the ship, must it mean you are abandoning the other sailors?

Geoff stands up. He looks the same as always, with his deep-set brown eyes, dark beard and plain-brown country haircut—except for the eyebrows, I notice, which are darker and bushier and create a shelf so that his eyes are hidden in shadow, just glints. He brings out a fake-leather yellow suitcase with rusted locks and peeling decals secured by a heavy nylon strap. Barby’s stuff, what is left of it; in fact, her entire archive. Barby left it with him almost two years ago when, evicted from her apartment in Knoxville, she moved to Seattle to live near me.

Barby rolled her eyes and pointed at her lap. Uh, oh. The airport wheelchair appeared to be leaking. Barby sucked hard on an Old Gold. We had passed three bathrooms between the gate and baggage claim. Three times, Barby had claimed she did not need to go.

A little puddle formed on the dirty grey cement. Barby smirked, took another long drag, and gazed at passing cars with smoke leaking from her nose. The puddle trickled toward the curb.

Geoff lays the yellow suitcase on the coffee table. His hands are a slightly larger version of David’s. I look at mine. The same, Dick’s; I wish I had Barby’s. Geoff says he wants to show us how beautiful Grandma Butch (Barby’s mother) was. He takes off the strap, unlatches the rusty clasps, and lifts the lid. The smell of stale cigarette laced with mildew rises into the room like a genie wafting out of a bottle. We are silent.

Over the next hour we pluck out photos: sort, stare, show each other. We build our separate piles, from our yearly visits to Barby’s beach in the 1970’s. I think about those ashes again; they belong to all of us; they might help bring us together. But still I do not bring them out.

I grab a random snapshot of Barby standing on the lawn on Bundy Drive in the ‘50’s showing off her new, short haircut, called a ducktail. Her head is tilted. She wears a satisfied smile.

Why not? Barby would say, spiraling her right forefinger in the air in a tight circle and then swooshing it up and away. Barby was learning shorthand, a stab at practicality for this summa cum laude Phi Beta Kappa. Her simper said it was a cute trick. You knew she was never really going to be a secretary.

Finally, Geoff suggests we stop and he closes the lid. We move on to more wine and David’s lasagna. Later, Bruce, Geoff, David and his wife, Anne, settle at the dining table to play Pit and Liars’ Dice, games from our childhood, and I envision the competitive steam from our childhood. I am not a good loser, I never was, and I usually lost—and I am tired—so I retreat to my room to read.

But first I say, on impulse, “Would it be okay if I took that yellow suitcase home with me? After we’re all done?”

They look up. Anne shuffles the cards.

“Sure,” Geoff says.

Bruce shrugs and nods.

David nods.

I can take the yellow suitcase home with me.

I will use that archive to investigate Barby’s life, something I know almost nothing about. I will use it, photos and papers, to write her story. And I will paint portraits of Barby, too, lots of them. But I do not know that yet. I just want the yellow suitcase.

Night night, sleep tight—I tensed—don’t let the bedbugs bite! Dick pinched my arm. He chuckled.

I liked it better when Barby patted my shoulder: night night, Patty.

We spend the next day exploring Monterey County like pilgrims in the Holy Land. You can tell David is proud, as though it’s his. Near Big Sur, we sight sea lions, sea otters, pelicans, and then a spout, and then lots of spouts, out near the horizon. In David’s scope the barnacled backs of gray whales migrating to Baja to have their babies heave into view.

Barby’s mothering may have been absentminded, but one thing all four of us got, and we got it from her, is this capacity for enchantment with nature.

Across Highway One, we take a hike up Soberanes Canyon: Redwood and manzanita in the ravines, prickly pear on the slopes, and everywhere horsetail fern, coyote bush, shooting stars, and sticky monkey flowers. Bruce doesn’t want to cross the wooden bridges over gold-flecked Soberanes Creek. I have to coax, I hold his hand. Bruce was born with a stiff, permanently contracted right arm and right leg, probably the result of a difficult forceps delivery—spastic diplegia, it was called. This is the first time I’ve realized that, because of his shriveled foot and uneven gait, he does not trust his balance.

We eat apples and trail mix on Rocky ridge with the sun warm on our backs and the Pacific below.

On the way back to town, we make a quick stop at a copse of eucalyptus in Pacific Grove, just in case. The canopy is coated—coated—with Monarch butterflies, like orange-and-black leaves that unfold and flicker sunlight with silken whispers. A peak experience, Geoff mutters. He and Barby were butterfly collectors.

Finally, we pay a visit to Ventana Vineyards, in the foothills of the Santa Lucia range, to watch the sun set while we sip sauvignon blanc. They just give you this? For free? They don’t charge for this? We find Geoff’s amazement very funny, our genius physicist bumpkin brother. Maybe Barby gave us her enchantment with wine, too. For her, it was nearly lethal.

That night, like a kid calling in the last outliers in a game of hide and seek, David sings out, rings of Saturn, Jupiter’s moons, and we crowd onto the deck to take turns one more time at the scope: rings of Saturn, Jupiter’s moons, in Del Rey Oaks’ clear winter skies.

Whales, wildflowers, butterflies, wine and planets. These are what bring us together, wrap us in happy wonder. And though Barby was not mentioned, she was with us all day. Barby loved California.

We set off the next morning in the rented Chevrolet, everyone soft and generous about who gets which seat. We steer onto Highway One, the old snaky coast road—eight hours to L.A., but it was the road of our childhood, and it has the gunmetal Pacific Ocean on one side, and silver, olive, and jade chaparral on new-pea foothills on the other. Red rock. Black conifers. I always feel hopeful when I see the smudge-line where ocean meets sky.

But then Geoff inserts country music, Alabama, into the tape deck and our sweet, delicate accord deteriorates: Bruce says something funny—Bruce is very funny—but it has bite, and Geoff, who has one of those faces you can’t read so you read it as arrogant, stares at him in the rear-view mirror without speaking. I am in the back seat with Bruce; I start vibrating with his prickle. I wish I were the kind of person who could tune that stuff out, but I’m not. Finally David and I generate a rule that the driver should get to pick the music and Bruce curls into a slouch, his mouth a horizontal thread. Now the silence is not tranquil.

And I was already getting tense. Geoff drives too fast. They all do.

Later, when Bruce is driving, he puts in some loud rock music. Geoff, now in back, protests. Bruce pauses the tape. Do we have a rule or don’t we? Okay then. Bruce again blares Led Zeppelin. The atmosphere in the car has become noxious, as though oxygen is in short supply, and my stomach clenches. I need something, like my own tapes, maybe the Goldberg Variations. Why didn’t I bring tapes? I think about those ashes in the trunk. I want Barby. This longing surprises me. I never believed Barby was on my side. I would have said she liked the boys better, and David best. I find out later they always thought she favored me.

But did Barby ever settle our squabbles? Did she soothe us? Four kids.

Finally, after seven-and-a-half hours, we hit L.A. County. Geoff is again at the wheel. Right at County Line beach, right where we set off Fourth of July fireworks when we were little, he inserts a new tape. Oh dear, I think, now what?

The piercing guitar and sweet harmonies of the Beach Boys’ Surfin’ Safari burst forth, loud and ringing, and instantly we are bouncing, all four of us, bouncing high in our seats; and singing, too, like on ancient family car trips. I glance at Bruce’s bobbing, grinning face and grab his hand. I look at Geoff in the rearview mirror, and at David—we are also weeping, all four of us, but weeping can’t stop us. We chant, we shout, we shriek, Help Me Rhonda, Good Vibrations, Surfin’ USA past the sere hills of Malibu, past Topanga Canyon and Sunset Boulevard and Will Rogers State beach; Wouldn’t It Be Nice past Chatauquah Boulevard and the cliffs along the Pacific Coast Highway. Together again, all the way into Santa Monica. And Barby would have sung along. She loved music, any music, including our music. She sang harmony.

That night, in a modest hotel on Ocean Avenue, I place my box of ashes on the nightstand and I stand there, palm on top, until the paper grows warm. Then I slide my bare legs between cool, pilled sheets and turn off the light. I roll the stiff pillow. I am too worn out to read, too tired to dream.

Ollie ollie oxen free free free. Robin song, eucalyptus, orange blossom and dust. Barby’s musical lilt called us in. Ollie ollie oxen free free free.

The next morning we meet in the lobby wearing shorts and sweatshirts over bathing suits. We carry identical white hotel towels, and I carry the white box. No one comments on the box. I also carry four copies of a poem, Rilke’s Ninth Duino Elegy. We amble, silent, two blocks along Ocean Avenue to a steep little alley called Pacific Terrace, down to Appian Way, then two more blocks to the Sea Castle, Barby’s last home in California. The temperature is in the sixties, the sun a pale disc behind morning marine air.

The Sea Castle is gone. My throat constricts. The pink, art deco high-rise is gone, replaced by a sleek steel and glass structure called the Sea Castle Luxury Suites. Why would they tear it down? We had loved the rent-controlled Sea Castle, with its assortment of grizzled eccentrics, mothers on welfare, and old ladies. Barby claimed Joan Baez lived in the penthouse on top, though we never saw her. We did like to watch the surf bums who lived in white vans in the parking lot—in fact, David had once lived in his white van in that parking lot. If you got there early enough, you could catch them rousting out of side doors, their ecstatic teeth and far-away eyes gleaming in bronzed faces. Beach coyotes, they would lope to the ocean with their toothbrushes. Their hair looked like the cellophane hair of dolls.

We trudge through the half-empty lot, now devoid of ratty vans, to the fresh asphalt boardwalk, now called Ocean Front Walk, and down the same old concrete steps onto cool, soft sand. Far away down the beach, two orange beach-cleaners chug toward Venice Beach.

We sit on a shelf formed by the night’s high surf and we gaze at the grey-scrimmed waves. No one speaks. Finally, I read the Elegy.

Why, if this interval of being can be spent serenely

in the form of a laurel, slightly darker than all

other green, with tiny waves on the edges

of every leaf (like the smile of a breeze)–:why then

have to be human—and escaping from fate,

keep longing for fate.

I tell them how I found this poem on my computer the morning after Barby died, in My Documents, and how I had not put it there, and Wayne, my husband, had not put it there, so I decided it was a message and a gift. And how I told Wayne it was proof that God was in the computer, and how Wayne said, only half joking, don’t tell anybody, and how I told everybody. How I read it at Barby’s memorial, read it to all my friends, read it to colleagues, read it every evening to myself. (David’s wife, Anne, had typed out the poem for her collection on her last visit and accidentally saved the file. Learning this later in no way diminished my miracle.)

Earth, isn’t this what you want: to arise within us,

invisible? Isn’t your dream

to be wholly invisible someday?—O Earth: invisible!

What, if not transformation, is your urgent command?

Transformation. Urgent command, I say again, and I hand them their copies. My breath grows shallow. My chest feels as though it is wrapped with wire.

We tell stories, the old standards: cows eat dirt, all through train go home now, ice cream tastes good with napkin. We each pitch memories into the pot, but our supply is so small. Geoff, and especially David, can’t remember much about Barby before her nervous breakdown. I want to give them something, but nothing comes.

Some sniffling, a few tears. Silence. Bruce makes us laugh, reminding us how Barby was just like Lucy on I Love Lucy. It’s time.

I pass the box of ashes to Bruce, who hefts it and rattles it. He passes it to David, who hefts, and David passes it to Geoff, to be hefted, rattled. They pass it back. I hold out my hand, but Bruce un-tapes the white paper, flips up the lid and grabs a fistful with his left hand, his good hand. He extends the box to me in the crook of his right arm.

Bruce marches to the water and stands ankle-deep, a lone figure facing the heaving, leaden ocean with his arm raised. He leans over and lays his ash on the sea. Some of the ghostly powder blows away, some rests atop the creamy foam. Bruce appears to taste his hand.

He turns around and limps back to our shelf, his mouth upside-down. Geoff wraps his arms around him and they sob. I cling to David for a moment, and then I take some ash. I walk to the water. Sprinkling her ashes through my fingers as though I am spreading grass seed, I say softly, here you go, Barby. After a minute, I turn around. Three pairs of eyes are watching me; three stripped faces.

Bruce wails, “I thought we were only going to say good stuff. But she was a terrible parent. We all had a hard time, a terrible time. And I will do better than that.” Very fierce, “I will be better.”

Geoff, who has recently had hard times of his own, says, “Well, but she is like us, we are like her. She did the best she could.” Bruce is sobbing. I don’t know what he hears.

As though he has no choice, Geoff picks up the box. Maybe in a family that falls apart too soon, marching in birth order is a way to resurrect, to concoct, tradition. Or maybe all families, fallen-apart or not, do things in order. Geoff scoops, strides to the water, and flings the ash, like a cloud, at the surf. The cloud flies apart; tiny fragments rain down. The bone. When Geoff turns around his cheeks are coated with tears.

David takes his turn. With the light steps of a cat, he jogs to the sea and lays his handful of ash on the foam with the rest.

Then we all just bawl. Together.

The first time we lost Barby, thirty-four years ago, we blew apart. We shriveled, stunned and silent, into our separate shells. We moved away, from her, from each other, and sooner or later, from L.A. Now we stay together. We hug, we look at each other. David’s round brown eyes swim, his lower lip quivers; Geoff’s face morphs into a gaping mouth and injured brow; I don’t squelch my crumple and hiccup; and Bruce, the expressive one, our Pavarotti of grief, spews saliva and snot and tears and words, though I don’t follow. I think, we’ve never cried together, but then I remember just yesterday we cried with the Beach Boys.

Later, on the drive home, David will say that we salvaged a family on that beach.

I will say we created a family.

Geoff will say we’re both right.

When our tears are spent, we just sit side-by-side, staring at the sea. The ash on the foam has not dissipated. I watch it slide toward me, and away.

But I guess we were too frugal, because when I check the box, it is still half-full. I give the boys a look. Bruce smiles, the green-glass of his eyes startling against red rims. I jerk my chin at him and say I want someone to go in so I will have to. We all stand up. I pull my sweatshirt over my head. Bruce shrugs and says something like, well, here goes. He grabs a handful of ash, dashes into the surf with his lopsided sprint, and dives under a roller. He jets up on the other side, howling.

I am right behind him. I dive—it is so cold—and the icy ocean snatches my tears, leaving me empty and clean. I shake my hair and dive again and this time I open my hand, and Barby’s ashes bloom into the salty water. I pray to the ocean gods, take her to China, she would love to see China.

Geoff, and then David, slam into the waves beside me. We all leap and scream and chortle and snort; windmill arms and whip water. We grin at each other, born-agains in the surf. We are proud to be the only people at the beach. Angelenos, they call us.

Pretty soon, I get out. I feel like a chicken. But I am too cold.

Years later, on the phone, Bruce will tell me, “I talked to her out there. I remember, I was standing in the water up to my chest—it was so cold. But she was there. I talked to her. And I told her, it’s not your fault.” He paused to snuffle and clear his throat. “It wasn’t her fault,” he cried, his voice high. “It’s like, our family was five kids and one really horrible parent.”

Of course, I thought. That’s it. Dick was the horrible parent. Barby was one of us.

We sit again on the shelf of sand wrapped in white towels, hunched-up and shivering. We aren’t ready to leave the beach. We watch the scrim of foam, now top-lit by the sun, slide toward us, and away. I pick up the box.

I have a fleeting thought that we should have used some ash to create a ritual, swiped a bit on each other’s foreheads—but no. We did what Barby did; we did the best we could. And those ashes are gone.

To China.

Honeymoon, Ontario, Canada

“She Would Love To See China” first appeared in (em) Review of Text and Image, issue one, Fall 2012.